Richard Dawson - Clapham Grand, 29 - 30.04.2025

These are sentiments rarely heard in lyrics, from characters we rarely, if ever, hear from.

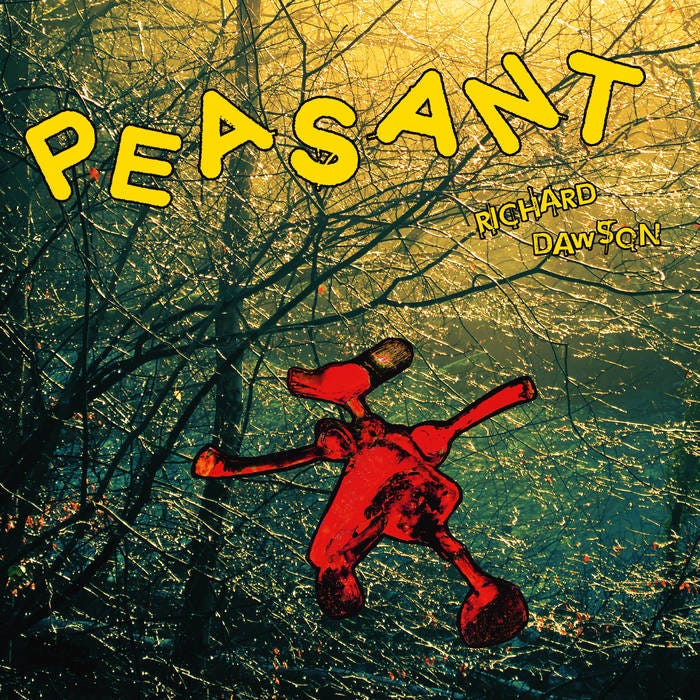

Peasant (2017), Richard Dawson’s “breakthrough” album, is that rare thing: a concept album in the truest sense of the word. The album takes a fantasy version of the medieval history of Northumbria as its backdrop, and each track takes the name of a character from that kingdom — “Beggar”, “Weaver”, “Scientist” — providing lyrical snapshots of these figures over an experimental folk frame.

Thematically then, Peasant is an intriguing re-hash of the 1970s prog-rock-folk movement; perhaps the least modish and most parodied genre of all time. Yet unlike his 70s counterparts — with their Tolkien-esque quests and battles — Dawson’s songs on Peasant place the emphasis on quotidian details, which serve to draw our attention to his character’s interiority and emotional struggles.

Take “Soldier”, where the central character is more concerned with affairs of the heart than the battle at hand:

Here we are at the Fortress of Long Winds

My fellows bristling with anticipation

And slurp among their supper bowls

A map of steam in the rafters overhead

Shovelling it in I don’t taste a thing

Only a memory of kisses spilled upon my chin

I am tired, I am afraid

My heart is full of dread […]

I am running for my life

Avowed to never draw another blade

“Soldier" had, in fact, been released by Dawson six years previously with entirely different lyrics. “I Am Not Your Man”, as it was then called, went more like this:

Here we are, after all these years

I cannot shake this lovely ache

I’m very tired of dreaming.

And even though you are always on my mind

I can finally see the day has come for me

To say goodbye to everything that I believe

I remember, I am aware

I am not your man.

The earlier version is a far more typical love song, which we can assume is narrated from the perspective of the actual singer. There is no real setting. Where we are is abstract: “after all these years” is a time, not a place like “The Fortress of Long Winds”. Nothing is “overhead”. There also aren’t really any verbs: no “bristling”, no “slurping”, no “shovelling”. No mention of blades.

The later version turns up the specifics, the physicality and the movement to create something more narratively complex and unique, enhancing, rather than distracting from, the feeling at hand.

Accordingly, on Dawson’s follow-up to Peasant, the presciently titled 2020 (it was released in 2019), the medieval context is gone, but the lyrical approach and affect is consistent. Tracks like “Fresher’s Ball” are packed with locations, verbs and action, if in a more subtle, more contemporary mode:

I drove Bobbie down to university

With the Rover bursting at the seams

We brunched in the halls of res canteen

Then I got on my way

Waving me goodbye from the steps of her building

She shrinks into the shudders of the rearview

Tears begin to fall on the outskirts of Leeds

I am missing her already

2020 dials the details in further, focusing on regular, rather than exceptional or fantastical events. Yet these events still add up to a conceptual whole: while never didactic as such, tracks on 2020 like “Jogging”, “Civil Servant” and “The Queen’s Head” all bring a certain state-of-the-nation address with them, an appeal for community in the context of anxiety and local malaise.

On “Jogging”, we begin with an individual stuck at home:

Recently I've been struggling with anxiety

To the point I find it hard to leave the flat

The days drain away, scouring eBay

Or looking on Zoopla at houses where I'll never live

Soon, the speaker tells us about an event that symbolises political turmoil, powerlessness and racially-motivated hate, concluding: “It's lonely up here in Middle-England” before we’re left on a quiet, if uplifting note:

Would you like to sponsor me

For running the London Marathon?

Though it's really daunting

We're aiming to raise a thousand Pounds

For the British Red Cross

Like other great social realists, many of Dawson’s snapshots on 2020 work synecdochally: they are small, symbolic examples, implying or critiquing a larger political structure.

Dawson’s latest effort, End of the Middle (2025), however, eschews conceptual framing and grand narratives. It’s a comparatively subtle record; more existential than political. Songs conclude but never resolve or summarise. I can’t help but feel that the title “End of the Middle” is in fact a comment on his own work: an end to both the Middle Ages and Middle England narratives Dawson has most famously put forwards. Because, unlike Peasant or 2020’s occasional forays into wider commentary, the vignettes here never stand in synecdochally for something larger, some concept or edifying point, but are simply ends in and of themselves.

A man gets drunk at a wedding on “Knot”. Someone tends to their allotment, while caring for a partner on “Polytunnel”. And on “Removals van” a house move brings painful childhood recollections back to the surface. No meta commentary enters, we simply sit with these people and their actions for a while.

“I still can't believe I'm a grandma” Dawson sings on “Gondola”:

Jen just passed her driving test

I’m going to put a couple of thousand pounds towards a car

And take her on holiday, make memories before it's all too late.

These are sentiments rarely heard in lyrics, from characters we rarely, if ever, hear from. When he renders them in song, Dawson lends them a kind of gravity, a kind of dignity even, deftly weaving existential questioning into the fabric of the most mundane experiences:

Cash In The Attic, A Place In The Sun

A very long-overdue phone call from my son William

Deal Or No Deal, or no deal, or no deal, or no deal

Box number 17 is opened to reveal a wound that's never healed.

There’s something novelistic or fiction-esque about Dawson’s writing, then. And like many great short stories, End of the Middle’s existential moments imply more than the sum of their parts, but to what end? It’s an effect that puts me in mind of the (recent nobel-prize winning) Jon Fosse’s writing, especially Scenes from a Childhood, a series of five short stories spanning 1987-2003. Fosse’s stories such as “I Just Can’t Get the Guitar Tuned” (an uncannily resonant example) present a snapshot of an event that stands for nothing. The drama, the tension is in the telling itself:

I just can’t get the guitar tuned and the dance is about to start. There’s already a big crowd in the room, most of them people involved with the event and their friends and girlfriends, but still a lot of people, when I look up from the shelter of the long hair hanging down over my eyes I see them moving around the room. I’m bent over my guitar, turning and turning a tuning knob, I turn it all the way down and the string almost dangles off the fretboard, all forlorn, and then I strum on it while I turn the knob up, up, I hear the tone slide higher, I strum on two strings, now is this right?

The scene ends with the character breaking his string, twice, before concluding that they’ll just have to press on:

I guess I’ll have to play with five strings, I say. That’ll probably work, he says.

People are already here, I say.

That’ll work, he says.

As so often in Dawson, things conclude, but don’t necessarily resolve. In Fosse, it’s not the individual stories, but the relationships between the stories that make the whole work. Similarly, in a recent interview (and despite his songs being hermetically sealed worlds, told in vivid detail) Dawson explained that it isn’t the individual song that he is focused on, but the relations between songs on an album, and the relationships between his albums. There’s plenty to dive into; multiple shades of songwriting. Albums mirror and echo each other, the connections are there for the finding.

“The pleasure of reading” novelist Tessa Hadley wrote recently, “begins in an excited stab of recognition, though we’re so often recognising people we’ve never met in places we’ve never been.” In Dawson’s work, we find this kind of recognition all the time. Whether in the story of a medieval soldier, an anxious jogger or an existential grandmother, he takes us further into people and places than most lyricists dare, or, I expect, are able to go.

Dawson plays the Clapham Grand on the 29th and 30th of April.

I will be there on the 30th- can't wait!!

Perfectly timed after a weekend of heavy Dawsoning! ‘Prostitute’ always weakens me — those chords he falls upon!!