Cantilever is a weekly rundown of London-based gigs and other musical ephemera.

This week’s playlist

Spotlight Shows

Fennesz - The Round Chapel, 11.04.2025

Components is a website / art-project / movement that substantiates cultural critique and philosophy with the analysis of large data sets. This is important because it brings philosophy into the 21st century. Where academic philosophy plays Wittgensteinian language games, often arcane to general readers, and critical theory makes exciting but unsubstantiated claims, Components’ forays into gaming, psychopharmacology, music, scholarship and tech, lead with the data and ask: what can we actually know about contemporary life based on the evidence?

Their latest essay, “Building Heideggerian AI”, uses data from AI research papers to ask how AIs are programmed to conceptualise intelligence. The discussion of AI specifically is worth reading in its own right, but the crux of the piece's philosophy is this:

“In his essay “Heidegger on the connection between nihilism, art, technology, and politics”, Dreyfus argues that to walk away from “The Question Concerning Technology” with Luddite reactivity is to miss the point. Technology has been with us since the beginning and will stay with us until the end — unequivocally opposing it is no more sensible than protesting cutlery. Instead, Heidegger was concerned by the “technological understanding of being,” in which the differences between all objects and people are flattened into a plane of total fungibility and subjected to “calculative thinking”, rendering everything as a resource that becomes a means to an end.”

Components argue that our prime ontological mode is an “aesthetic” one: when we listen to music, engage in art, spend time with our family and friends, these are not and should never be, means to an end. They are irreducibly valuable.

However, as we live our lives filtered through big tech, big pharma, and now big AI, it is possible to feel pushed hard towards a “technological understanding of being” where we see ourselves as merely useful objects inside a flat ontology.

This is an ethical argument, one of the most important of our times. Components position is crucial because it gives an object to anyone who feels there is something nihilistic, something spiritually absent about homo technologicus. Often discussions on technology and the self are about addiction — I can’t stop engaging with this thing that returns me little value — but Components help us see an increasingly insidious side at a societal level: what if, rather than returning no value, the value you hold yourself in, is in fact being reconstituted by these forces? Reconstituted in their image. Consume, network, disengage, scroll, flatten your experience of life, they seem to say.

Yet checking out entirely from technology needn’t be the answer. It is always possible, Components claim, to orient yourself towards an aesthetic mode of being by engaging in aesthetic experiences. This position really is, in my view, one of the best arguments for the “why?” of art that we have today:

”If the technological understanding of being upsets the proper direction of means and ends, an aesthetic understanding reorients them to their rightful positions.”

To hear an aesthetic understanding of being while wholeheartedly embracing technology, you could do worse than to start with the music of Fennesz, who plays the Round Chapel in April.

Fennesz’s album Endless Summer (2001) took the 1966 surf documentary of the same name as its template, recreating and processing its gentle surf rock soundtrack through a digital ether. The film — The Endless Summer — could not be any more analogue. The story of two pro surfers who follow the summer from the northern to southern hemisphere; there is no conflict to be found in the film. It’s just a cool vibe. Living in the moment, outdoors, doing what human beings do; a deeply aesthetic understanding of being on display. That is: the people are not doing something as a means to an end. Even the travellers’ quest isn’t presented as any great feat. They’re simply doing something because they want to feel joy in it.

Yet Endless Summer the album couldn’t be materially further away from the film. It is defined by its digital sound: hard stops, the sonic form of ones and zeros, a kind of aliasing static reminiscent of dial up tones, crash report signals and other general PC glitching. Listening to it, you are acutely aware that it was made on a laptop — yet the free spirited emotion of its source material still peeks through. Despite the backdrop of Y2K paranoia, Fennesz’s embrace of contemporary tech showed us that moving into the 21st century, our humanity would not be lost, but would nonetheless find new forms.

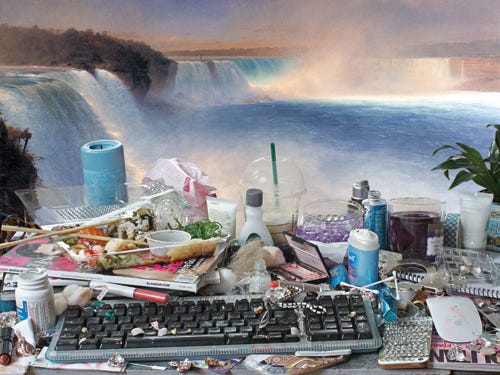

Fennesz’s music finds a visual art counterpart in the early collage work of Jon Rafman. In Rafman’s collages, personal items, junk and bric-a-brac litter a desk that can’t be seen, with a computer keyboard front and centre. Where the screen should be in front of this computer keyboard, there is none, only a beautiful beach vista, mountains, pastures new, a waterfall.

The point of the pieces is not to imply technology itself allows us to get to this ideal landscape, nor that it is preventing us from getting there. But rather, the figure-ground relationship seems to suggest that even if our technological interfaces are literally (in this case) front and centre, the background of what makes us human — the aesthetic experiences we strive for, typified by sublime outdoor scenes — is always there.

Ironically, the movement Rafman belongs to — the so-called second generation of net artists — gave itself the term “surf culture”; an ironic reference to “surfing the web”, but one that asks some of the questions of the spirit, of freedom, of human nature, that actual Endless Summer-esque surf culture seems to imply. “I was in search of sublime moments, but rather than in nature, it’s all mediated through the screen, posing the question of whether the sublime experience could still be had…” Rafman says of his work. The same could be applied to Fennesz.

Crucially, neither puts forward a Wall-E-esque vision of the sublime actually being available in a technologically mediated space — Plato’s shadows on the cave wall — an anodyne world of entertaining spectres, another form of Heidegger’s flat ontology. Technology should always be a tool for us to increase our stock of experience, never an end in itself.

In the first part of Being and Time (1927), Heidegger makes a distinction about tools. There are two ways of relating to a tool, he claimed. When we’re using, for instance, a hammer, it is “ready-to-hand”. When we simply observe a tool not in use, perhaps not knowing how to use it, it is “present-at-hand”. In the former, the object simply becomes part of the action, it recedes from cognition: we concentrate on the task, not the hammer. When something goes wrong, however, let’s say the hammer breaks, it returns to being “present-at-hand”. The broken tool returns to our cognition and we see it for what it really, objectively is: an object, a lump of metal and wood. We, as wielders, are the ones who give it purpose. The human being gives the object an end. But when “ready-to-hand”, we don’t think about what it really is, and perhaps, what we become when we use it. “We shape our tools, and thereafter our tools shape us” said Marshall McLuhan. I’m condensing something massive into a paragraph here, but the implication for our relationship to technology is vast.

What if we don’t want a particular tool to recede into the background of cognition? What if we force it to come out and show us what it really is?

Particularly with developing technologies, McLuhan’s timeline isn’t so clear-cut. We can continue to shape, to reconstitute, the tools we use in the image of an “aesthetic understanding of being”, the “thereafter” is always within reach: this is the essential Components argument for Building Heideggerian AI and why it’s so worth attending to.

So beyond just the “why?” of art then — to orient the individual away from the “technological” to the “aesthetic” understanding of being — there is an additional “why?” of art that in some way breaks and draws our objective attention to contemporary technology. By using digital tech in an unconventional, abstracted way, the artwork shatters its object’s material “ready-to-hand-ness” and lets us see it for what it really is.

Art like this disrupts our passive engagement with technology. It forces us to see digital tools not just as seamless extensions of ourselves, but as structures that shape our reality in ways we rarely question, or question only in a binary distinction — being online bad, going surfing and seeing the world good. Nothing is ever that simple.

MIKE - Earth, 06.03.2025

MIKE is relentless. Since 2017, he has put out at least one album per year, has embarked on a seemingly non-stop global tour, and he also releases all his material under his own record label, 10k. This independent bent means his relentlessness is necessary as well as intentional and artistic; as many artists respond negatively to the statement from Spotify CEO Daniel Ek — “it’s not enough to put out an album every three or four years” — many others, MIKE included, will simply adapt to the new musical economy without thinking about it too much, being no less authentic or principled for doing so.

MIKE openly acknowledges MF DOOM as one of his biggest influences, no doubt filtered through ex Odd-Future member Earl Sweatshirt, who is something of a mentor to MIKE. The pair met in 2016 when MIKE purchased one of Earl’s albums on BandCamp and struck up a conversation — when you value music, who knows what will happen!

MIKE and Earl move in tandem now. The beats and flow on MIKE’s 2017 release MAY GOD BLESS YOUR HUSTLE — especially standout track “Hunger” — feel like they could have fit seamlessly into Earl’s Some Rap Songs (2018), with their glitching, lurching, soul-sample-based beats and laconic deliveries. Since then, however, MIKE has explored a range of sounds, producers, and deliveries to see what sticks. Yet his latest album, Showbiz! (2025), feels like a return to that original template.

MIKE’s own account of his writing process heavily implies an imagistic mode: “It’s usually just free writing. I feel like the meaning kinda comes after, especially the more I spend time with it.” Meaning arrives from somewhere the artist doesn’t know. The rap isn’t there to pontificate statements, but to make us feel a certain internal truth. The artist only knows this truth once it has been spoken.

Despite its method, the imagist rap needn’t neglect commitment. As MIKE says: “A lot of what I peep now, especially through social media, is that people like to be like, “I don’t have no real opinion on anything.” I don’t know, I think it just makes it easier to kind of not stand for nothing. But I feel like what hip-hop is, if people really think about where the shit comes from, it’s just anti-establishment.”

Ephemera

Posh Isolation ceases operations as a record label

“We don’t even know what being a record label in 2025 means” say the Copenhagen-based founders, also referencing personal exhaustion. You and me both pal. Two Copenhagen shows will mark the end of the label.

Recently, within a year of each other, Posh Isolation mainstays Croatian Amor and Vanity Productions put out two records that dealt primarily with different sides of the experience of grief. Here are the descriptions verbatim along with links to listen.

“My younger brother died at birth and I never had a chance to meet him. Growing up he was my ghost friend, someone told me he lived in the stars which I accepted. I had not paid attention to him for many years but when I was making "Remember Rainbow Bridge” and waiting for my son to come into the world he suddenly appeared again. I partly dedicated Remember Rainbow Bridge to him, but I knew that it wasn’t his record, so I thought I should make one just for him and here it is; “A Part of You in Everything”, 8 songs about being human on Earth. I think it’s music which is best listened to at night out under the stars. Thank you to all my friends who helped making it!”

Upon what instrument are we two spanned?

And what musician holds us in his hand?

- Rilke

“The Night has passed already” is a new album by Vanity Productions. Recorded during the weeks after his sister’s passing, it resonates internally as the maelstrom of melancholy, transforming grief into distorted tunes. Minimalistic and bleak at the core, yet possessing vague and undeniable romanticism, morbid intensity and density. In that sense “The Night has passed already” is a tangible memo filled with love unexpressed, a ride through a tunnel drowning in light.”

Website Update

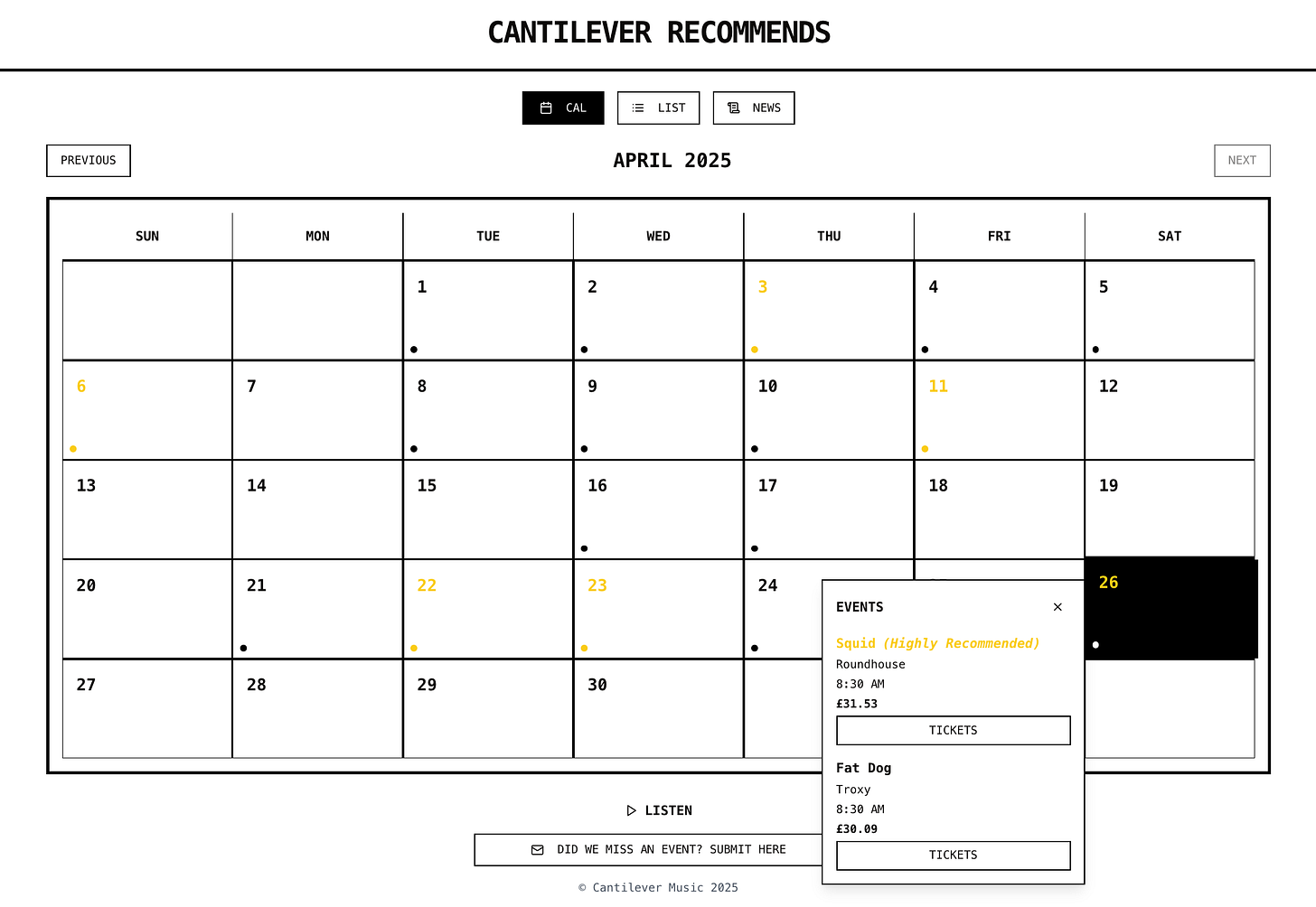

We’ve added the month of April to the Cantilever website. They say it is the cruellest month, and yet there are some frankly incredible shows coming up, including a new series by Scenic Route at the ICA —

”Scenic Route kick off their ICA hosted series that pays homage to collaboration: join us with live sets delving into musical, synchronisation and oscillation. Our first pair of pairs are Astrid Sonne x Fine as Coined and Jadasea & Anysia Kym both debuting their live sets.” —

The latter are MIKE collaborators and peers.

Plus Saturday the 26th which is already being described by this newsletter as the clash of the £30-per-ticket-slightly-avant-garde-high-energy-indie-rock-synth-bands.

cantilever strikes again. really appreciated this post - great playlist, great analysis. I just wish I lived in london.

thanks for linking that components essay. fascinating read. I wish I had read it before I published an essay last week about LLMs (https://robbieherbst.substack.com/p/machines-without-ghosts) that also incorporates Heidegger and wittgenstein. I make a similar argument, but I had no idea that H had this history in the development of GOFAI.